CBT

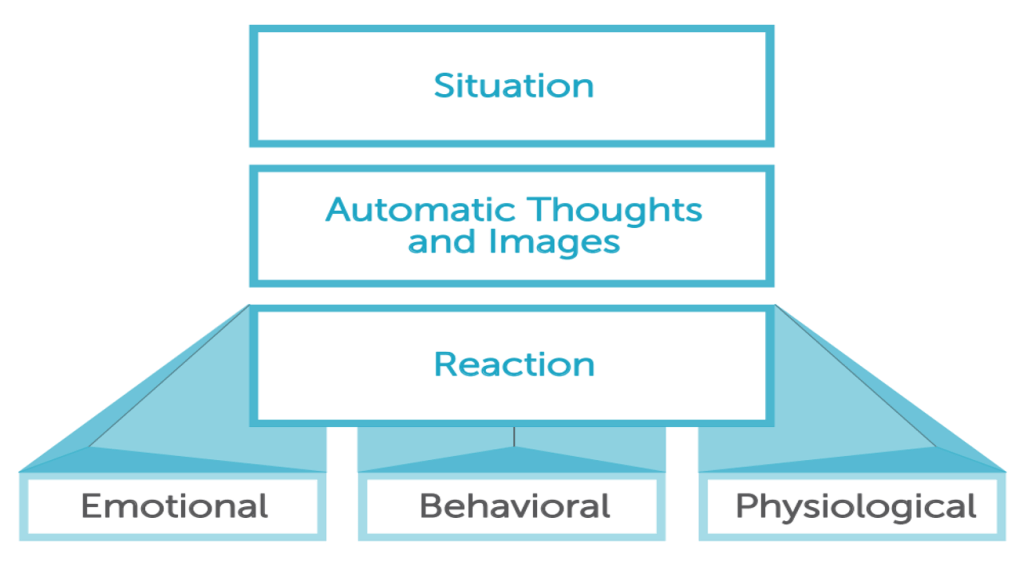

I would like to share some key insights regarding the principles and applications of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). As devised by Beck, CBT is a structured, short-term, and present-oriented psychotherapy designed to solve current problems by modifying dysfunctional thinking and behavior.

The core of the cognitive model suggests that inaccurate or unhelpful thinking is common to all psychological disturbances. When individuals learn to evaluate their thoughts in a more realistic and adaptive way, they experience significant improvements in their emotional state and behavior. This process involves working across three levels of cognition:

– Automatic Thoughts: Superficial ideas that pop into the mind (e.g., “I can’t do anything right”).

– Intermediate Beliefs: Underlying assumptions (e.g., “If I try, I will fail”).

– Core Beliefs: Deep-seated views about oneself, others, and the world (e.g., “I am helpless”).

CBT has proven to be remarkably versatile and has been successfully adapted for diverse populations, cultures, and age groups. It is currently utilized in various settings—including hospitals, schools, and vocational programs—and is applied in individual, group, couple, and family formats. Furthermore, CBT techniques are increasingly used by a wide range of health care providers and specialists within brief appointments to foster enduring change.

8F

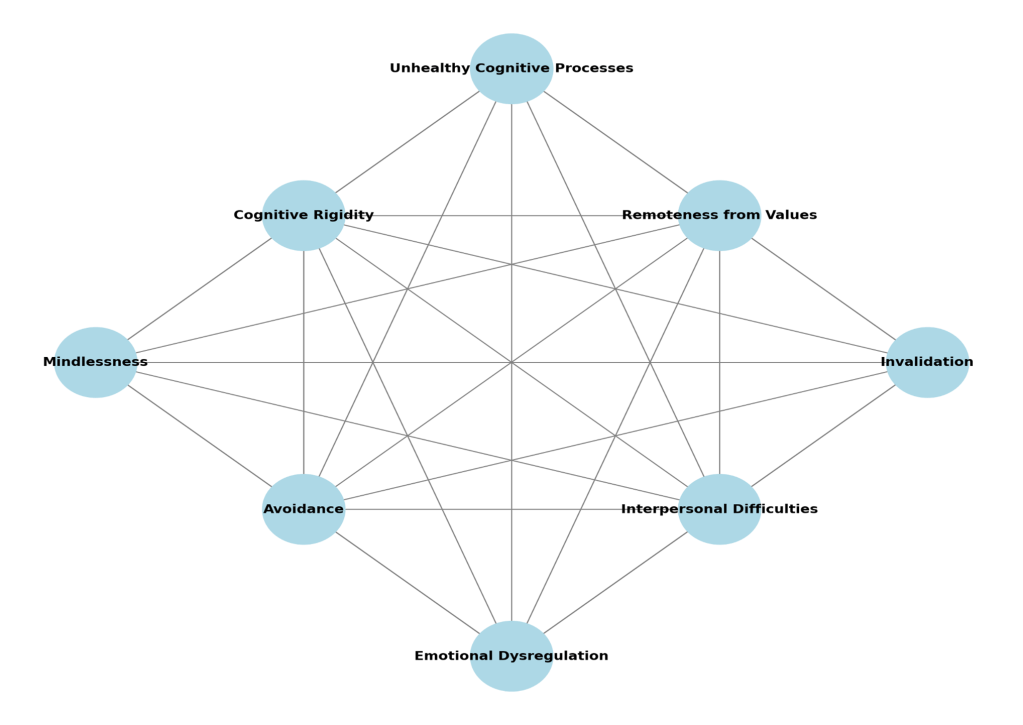

1. Cognitive Rigidity

Cognitive rigidity means having difficulty changing how you think, interpret situations, or adapt when new information appears. People with rigid thinking tend to hold on to familiar thought patterns and struggle to shift perspective, even when change would be helpful. This rigidity affects problem-solving, adaptability, and can maintain unhelpful beliefs. It’s linked to conditions like anxiety and mood disorders.

2. Emotional Dysregulation

Emotional dysregulation means struggling to manage emotional responses in a flexible, proportional way. Instead of experiencing emotions that fit the situation and then returning to baseline, reactions may be excessive, prolonged, or difficult to control. This can interfere with daily life and relationships.

3. Avoidance

Avoidance refers to efforts to escape or reduce uncomfortable internal experiences (like thoughts, emotions, or memories) or external situations that may trigger distress. While it provides short-term relief, avoidance often reinforces anxiety and maintains patterns of dysfunction.

4. Remoteness from Values

This factor describes a disconnection between a person’s lived behavior and their core values or personal goals. When people don’t act in ways that reflect what matters to them, they often feel unfulfilled, aimless, or anxious about their direction in life.

5. Invalidation

Invalidation occurs when a person’s thoughts, feelings, or experiences are dismissed or judged as unimportant by others or by themselves. It can be external (from others) or internal (self-criticism). Over time, invalidation undermines confidence, fosters shame, and disrupts emotional regulation.

6. Interpersonal Difficulties

Interpersonal difficulties refer to challenges in social interactions and relationships. Problems like ineffective communication, lack of assertiveness, and limited interpersonal skills make it hard to form satisfying and supportive relationships. These difficulties can increase stress and isolation.

7. Mindlessness

Mindlessness means being disengaged from the present moment. Instead of noticing sensations, feelings, and surroundings, attention is trapped in the past or future. This state disrupts effective coping, increases stress, and reduces enjoyment of life.

8. Unhelpful Cognitive Processes

This factor includes repetitive and uncontrollable thought patterns that maintain distress and interfere with adaptive functioning.

EMDR

EMDR is based on the idea that distressing experiences can become maladaptively stored in memory. When this happens, memories are not fully processed and remain “stuck” with the original emotions, body sensations, and beliefs. These unprocessed memories can later be triggered by reminders, leading to symptoms such as anxiety, flashbacks, emotional reactivity, or avoidance.

EMDR aims to help the brain reprocess these memories so they are integrated in a more adaptive way. The memory is not erased, but it becomes less emotionally charged and no longer dominates present experience.

How EMDR works

During EMDR sessions, the client focuses on:

- A specific distressing memory

- The associated negative belief (for example: “I am not safe”)

- Emotions and body sensations linked to the memory

At the same time, the therapist applies bilateral stimulation, most commonly through guided eye movements, but sometimes through alternating sounds or taps. This dual attention process helps activate the brain’s natural information processing system.

As reprocessing occurs, clients often notice:

- Reduced emotional intensity

- New insights or perspectives

- A shift toward more adaptive beliefs (for example: “I survived” or “I am safe now”

ACT

ACT is built on the idea that psychological suffering is often driven not by painful internal experiences themselves, but by how much we struggle with them. When people try to avoid, suppress, or control unwanted thoughts and emotions, those experiences tend to become stronger and more limiting over time.

ACT helps clients develop psychological flexibility, which means the ability to stay present, open to internal experiences, and committed to behaviors that align with personal values, even when things feel uncomfortable.

The core model of ACT

ACT is commonly explained through six core processes, often called the hexaflex:

- Acceptance

Making room for uncomfortable thoughts, emotions, and sensations instead of fighting them. - Cognitive defusion

Learning to step back from thoughts and see them as mental events, not absolute truths. - Being present

Developing mindful awareness of the here and now, rather than getting stuck in the past or future. - Self as context

Accessing a stable sense of self that observes experiences without being defined by them. - Values

Clarifying what truly matters and what kind of person one wants to be. - Committed action

Taking meaningful steps guided by values, even in the presence of fear or doubt.

Together, these processes support more flexible and adaptive functioning.

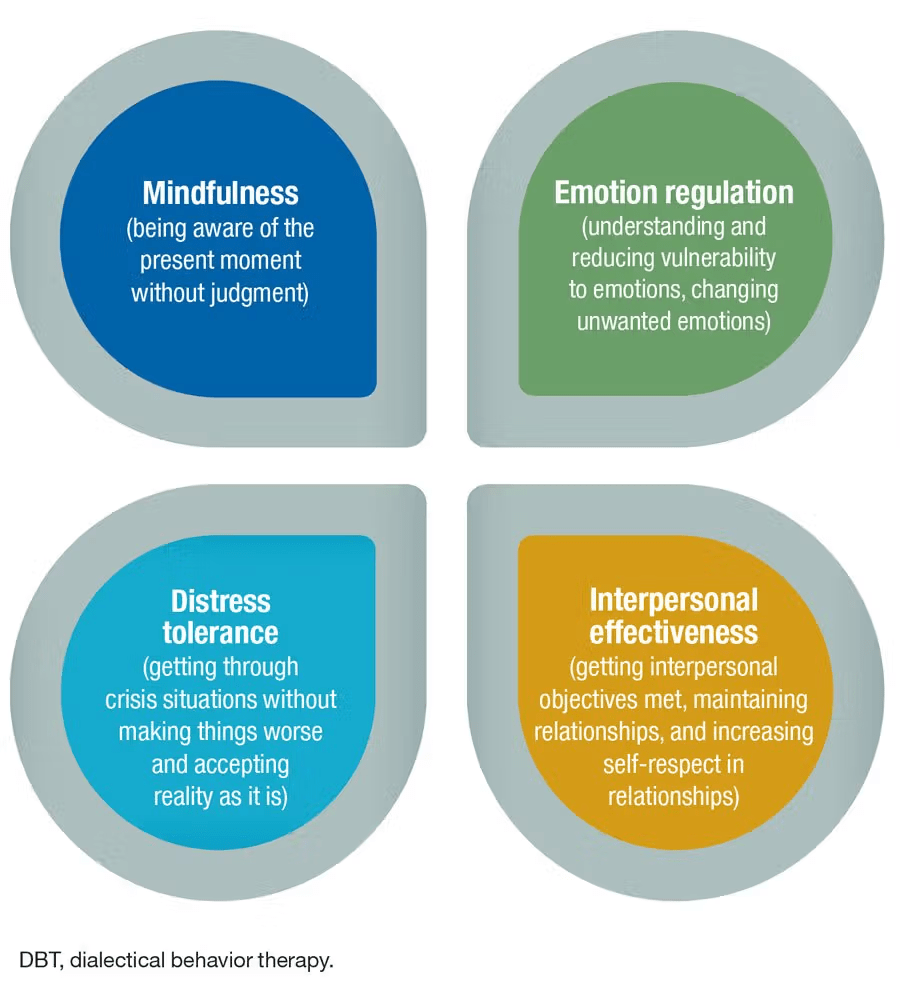

DBT SKILLS

CFT

CFT is designed to help individuals develop compassion for themselves and others as a means to regulate emotion, reduce psychological suffering, and improve overall mental well-being. It is particularly effective for those dealing with high self-criticism, chronic shame, or early attachment trauma.

The model is built on several key theoretical foundations, including:

– Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

– Evolutionary psychology and Neuroscience

– Attachment theory

– Mindfulness

A central component of CFT is the “Three Emotion Regulation Systems,” which categorizes emotions into the Threat system (fear/anxiety), the Drive system (achievement/pleasure), and the Soothing system (safety/calm). The goal of the therapy is to strengthen the soothing system through techniques such as compassionate imagery, soothing rhythm breathing, and developing the “compassionate self.”

Evidence shows that this approach helps increase self-compassion and emotional resilience while reducing shame and depression.

You must be logged in to post a comment.